Difference between revisions of "Documentation:Tutorial Section 3.1"

Jholsenback (talk | contribs) m (removed famous quote(s) in 2 places) |

Jholsenback (talk | contribs) m (heading chages) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

<!--<indexentry "Shapes, polygon based">---> | <!--<indexentry "Shapes, polygon based">---> | ||

| − | ===Mesh Object=== | + | ====Mesh Object==== |

<!--<indexentry "mesh, tutorial">---> | <!--<indexentry "mesh, tutorial">---> | ||

<p>Mesh objects are very useful because they allow us to create objects | <p>Mesh objects are very useful because they allow us to create objects | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

chesmsh.pov</code>.</p> | chesmsh.pov</code>.</p> | ||

| − | ===Mesh2 Object=== | + | ====Mesh2 Object==== |

<p>The <code>mesh2</code> is a representation of a mesh, that is much more | <p>The <code>mesh2</code> is a representation of a mesh, that is much more | ||

like POV-Ray's internal mesh representation than the standard <code>mesh</code>. | like POV-Ray's internal mesh representation than the standard <code>mesh</code>. | ||

| Line 233: | Line 233: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | ===Smooth triangles and mesh2=== | + | =====Smooth triangles and mesh2===== |

<p>In case we want a smooth mesh, the same steps we did also apply to the | <p>In case we want a smooth mesh, the same steps we did also apply to the | ||

normals in a mesh. For each vertex there is one normal vector listed in | normals in a mesh. For each vertex there is one normal vector listed in | ||

| Line 306: | Line 306: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | ===UV mapping and mesh2=== | + | =====UV mapping and mesh2===== |

<p>uv_mapping is a method of 'sticking' 2D textures on an object in such a way that it | <p>uv_mapping is a method of 'sticking' 2D textures on an object in such a way that it | ||

follows the form of the object. For uv_mapping on triangles imagine it as follows; | follows the form of the object. For uv_mapping on triangles imagine it as follows; | ||

| Line 388: | Line 388: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | ===A separate texture per triangle=== | + | =====A separate texture per triangle===== |

<p>By using the <code>texture_list</code> it is possible to specify a texture per triangle | <p>By using the <code>texture_list</code> it is possible to specify a texture per triangle | ||

or even per vertex in the mesh. In the latter case the three textures per triangle will | or even per vertex in the mesh. In the latter case the three textures per triangle will | ||

| Line 451: | Line 451: | ||

<code>mesh2</code>. uv_mapping is supported for texturing using a <code>texture_list</code>.</p> | <code>mesh2</code>. uv_mapping is supported for texturing using a <code>texture_list</code>.</p> | ||

| − | ===Polygon Object=== | + | ====Polygon Object==== |

<!--<indexentry "polygon, tutorial">---> | <!--<indexentry "polygon, tutorial">---> | ||

<p>The <code><!--<linkto "polygon">polygon</linkto>--->[[Documentation:Reference Section 4.2#Polygon|polygon]]</code> object can be used to create any planar, n-sided | <p>The <code><!--<linkto "polygon">polygon</linkto>--->[[Documentation:Reference Section 4.2#Polygon|polygon]]</code> object can be used to create any planar, n-sided | ||

| Line 579: | Line 579: | ||

===Other Shapes=== | ===Other Shapes=== | ||

<!--<indexentry "Shapes, other">---> | <!--<indexentry "Shapes, other">---> | ||

| − | ===Blob Object=== | + | ====Blob Object==== |

<p>Blobs are described as spheres and cylinders covered with "goo" | <p>Blobs are described as spheres and cylinders covered with "goo" | ||

which stretches to smoothly join them (see section "<!--<linkto "Blob">Blob</linkto>--->[[Documentation:Reference Section 4#Blob|Blob]]").</p> | which stretches to smoothly join them (see section "<!--<linkto "Blob">Blob</linkto>--->[[Documentation:Reference Section 4#Blob|Blob]]").</p> | ||

| Line 677: | Line 677: | ||

strength of two spherical components is overlapping there.</p> | strength of two spherical components is overlapping there.</p> | ||

| − | ===Component Types and Other New Features=== | + | =====Component Types and Other New Features===== |

<!--<indexentry "New Features, component types">---> | <!--<indexentry "New Features, component types">---> | ||

<p>The shape shown so far is interesting, but limited. POV-Ray has a few | <p>The shape shown so far is interesting, but limited. POV-Ray has a few | ||

| Line 736: | Line 736: | ||

component's interaction with its fellow components. In fact, next let us | component's interaction with its fellow components. In fact, next let us | ||

give this fellow something to interact with, shall we?</p> | give this fellow something to interact with, shall we?</p> | ||

| − | ===Complex Blob Constructs and Negative Strength=== | + | =====Complex Blob Constructs and Negative Strength===== |

<!--<indexentry "Blob Constructs, complex" "Negative Strength, blob">---> | <!--<indexentry "Blob Constructs, complex" "Negative Strength, blob">---> | ||

<p>Beginning a new POV-Ray file, we enter | <p>Beginning a new POV-Ray file, we enter | ||

| Line 812: | Line 812: | ||

knowledge of blob mechanics to make a wide array of smooth, flowing organic | knowledge of blob mechanics to make a wide array of smooth, flowing organic | ||

shapes!</p> | shapes!</p> | ||

| − | ===Height Field Object=== | + | ====Height Field Object==== |

<!--<indexentry "height_field, tutorial">---> | <!--<indexentry "height_field, tutorial">---> | ||

<p>A <code>height_field</code> is an object that has a surface that is | <p>A <code>height_field</code> is an object that has a surface that is | ||

| Line 911: | Line 911: | ||

<p>Wow! The Himalayas have come to our computer screen!</p> | <p>Wow! The Himalayas have come to our computer screen!</p> | ||

| − | ===Isosurface Object=== | + | ====Isosurface Object==== |

<!--<indexentry primary "isosurface, tutorial">---> | <!--<indexentry primary "isosurface, tutorial">---> | ||

<p>Isosurfaces are shapes described by mathematical functions.</p> | <p>Isosurfaces are shapes described by mathematical functions.</p> | ||

Revision as of 07:36, 25 March 2010

|

This document is protected, so submissions, corrections and discussions should be held on this documents talk page. |

Polygon Based Shapes

Mesh Object

Mesh objects are very useful because they allow us to create objects containing hundreds or thousands of triangles. Compared to a simple union of triangles the mesh object stores the triangles more efficiently. Copies of mesh objects need only a little additional memory because the triangles are stored only once.

Almost every object can be approximated using triangles but we may need a lot of triangles to create more complex shapes. Thus we will only create a very simple mesh example. This example will show a very useful feature of the triangles meshes though: a different texture can be assigned to each triangle in the mesh.

Now let's begin. We will create a simple box with differently colored

sides. We create an empty file called meshdemo.pov and add the

following lines. Note that a mesh is - not surprisingly - declared using the

keyword mesh.

camera {

location <20, 20, -50>

look_at <0, 5, 0>

}

light_source { <50, 50, -50> color rgb<1, 1, 1> }

#declare Red = texture {

pigment { color rgb<0.8, 0.2, 0.2> }

finish { ambient 0.2 diffuse 0.5 }

}

#declare Green = texture {

pigment { color rgb<0.2, 0.8, 0.2> }

finish { ambient 0.2 diffuse 0.5 }

}

#declare Blue = texture {

pigment { color rgb<0.2, 0.2, 0.8> }

finish { ambient 0.2 diffuse 0.5 }

}

We must declare all textures we want to use inside the mesh before the mesh is created. Textures cannot be specified inside the mesh due to the poor memory performance that would result.

Now we add the mesh object. Three sides of the box will use individual textures while the other will use the global mesh texture.

mesh {

/* top side */

triangle {

<-10, 10, -10>, <10, 10, -10>, <10, 10, 10>

texture { Red }

}

triangle {

<-10, 10, -10>, <-10, 10, 10>, <10, 10, 10>

texture { Red }

}

/* bottom side */

triangle { <-10, -10, -10>, <10, -10, -10>, <10, -10, 10> }

triangle { <-10, -10, -10>, <-10, -10, 10>, <10, -10, 10> }

/* left side */

triangle { <-10, -10, -10>, <-10, -10, 10>, <-10, 10, 10> }

triangle { <-10, -10, -10>, <-10, 10, -10>, <-10, 10, 10> }

/* right side */

triangle {

<10, -10, -10>, <10, -10, 10>, <10, 10, 10>

texture { Green }

}

triangle {

<10, -10, -10>, <10, 10, -10>, <10, 10, 10>

texture { Green }

}

/* front side */

triangle {

<-10, -10, -10>, <10, -10, -10>, <-10, 10, -10>

texture { Blue }

}

triangle {

<-10, 10, -10>, <10, 10, -10>, <10, -10, -10>

texture { Blue }

}

/* back side */

triangle { <-10, -10, 10>, <10, -10, 10>, <-10, 10, 10> }

triangle { <-10, 10, 10>, <10, 10, 10>, <10, -10, 10> }

texture {

pigment { color rgb<0.9, 0.9, 0.9> }

finish { ambient 0.2 diffuse 0.7 }

}

}

Tracing the scene at 320x240 we will see that the top, right and front

side of the box have different textures. Though this is not a very impressive

example it shows what we can do with mesh objects. More complex examples,

also using smooth triangles, can be found under the scene directory as

chesmsh.pov.

Mesh2 Object

The mesh2 is a representation of a mesh, that is much more

like POV-Ray's internal mesh representation than the standard mesh.

As a result, it parses faster and it file size is smaller.

Due to its nature, mesh2 is not really suitable for

building meshes by hand, it is intended for use by modelers and file

format converters. An other option is building the meshes by macros.

Yet, to understand the format, we will do a small example by hand and go through

all options.

We will turn the mesh sketched above into a mesh2 object.

The mesh is made of 8 triangles, each with 3 vertices, many of

these vertices are shared among the triangles. This can later be

used to optimize the mesh. First we will set it up straight forward.

In mesh2 all the vertices are listed in a list named

vertex_vectors{}. A second list, face_indices{},

tells us how to put together three vertices to create one triangle,

by pointing to the index number of a vertex. All lists in mesh2

are zero based, the number of the first vertex is 0. The very first

item in a list is the amount of vertices, normals or uv_vectors it contains.

mesh2 has to be specified in the order VECTORS...,

LISTS..., INDICES....

Lets go through the mesh above, we do it counter clockwise. The total amount of vertices is 24 (8 triangle * 3 vertices).

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

24,

...

Now we can add the coordinates of the vertices of the first triangle:

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

24,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>

..

Next step, is to tell the mesh how the triangle should be created; There will be a total of 8 face_indices (8 triangles). The first point in the first face, points to the first vertex_vector (0: <0,0,0>), the second to the second (1: <0.5,0,0>), etc...

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

24,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>

...

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>

...

The complete mesh:

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

24,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //1

<0.5,0,0>, <1,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //2

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //3

<1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //4

<1,1,0>, <0.5,1,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //5

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //6

<0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>, //7

<0,0.5,0>, <0,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0> //8

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <3,4,5>, //1 2

<6,7,8>, <9,10,11>, //3 4

<12,13,14>, <15,16,17>, //5 6

<18,19,20>, <21,22,23> //7 8

}

pigment {rgb 1}

}

As mentioned earlier, many vertices are shared by triangles. We can optimize the mesh by removing all duplicate vertices but one. In the example this reduces the amount from 24 to 9.

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

/*as 1*/ <1,0,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 3*/ <1,0.5,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 4*/ <1,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 5*/ <0.5,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 6*/ <0,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 7*/ <0,0.5,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 8*/ /*as 0*/ /*as 2*/

}

...

...

Next step is to rebuild the list of face_indices, as they now point

to indices in the vertex_vector{} list that do not exist anymore.

...

...

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>,

<5,6,2>, <6,7,2>,

<7,8,2>, <8,0,2>

}

pigment {rgb 1}

}

Smooth triangles and mesh2

In case we want a smooth mesh, the same steps we did also apply to the

normals in a mesh. For each vertex there is one normal vector listed in

normal_vectors{}, duplicates can be removed. If the number

of normals equals the number of vertices then the normal_indices{}

list is optional and the indexes from the face_indices{} list

are used instead.

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>,

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

normal_vectors {

9,

<-1,-1,0>,<0,-1,0>, <0,0,1>,

/*as 1*/ <1,-1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 3*/ <1,0,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 4*/ <1,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 5*/ <0,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 6*/ <-1,1,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 7*/ <-1,0,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 8*/ /*as 0*/ /*as 2*/

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>,

<5,6,2>, <6,7,2>,

<7,8,2>, <8,0,2>

}

pigment {rgb 1}

}

When a mesh has a mix of smooth and flat triangles a list of

normal_indices{} has to be added, where each entry points to what

vertices a normal should be applied. In the example below only the first four

normals are actually used.

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>,

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

normal_vectors {

9,

<-1,-1,0>, <0,-1,0>, <0,0,1>,

<1,-1,0>, <1,0,0>, <1,1,0>,

<0,1,0>, <-1,1,0>, <-1,0,0>

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>,

<5,6,2>, <6,7,2>,

<7,8,2>, <8,0,2>

}

normal_indices {

4,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>

}

pigment {rgb 1}

}

UV mapping and mesh2

uv_mapping is a method of 'sticking' 2D textures on an object in such a way that it follows the form of the object. For uv_mapping on triangles imagine it as follows; First you cut out a triangular section of a texture form the xy-plane. Then stretch, shrink and deform the piece of texture to fit to the triangle and stick it on.

Now, in mesh2 we first build a list of 2D-vectors that are the coordinates of the

triangular sections in the xy-plane. This is the uv_vectors{} list. In the example we

map the texture from the rectangular area <-0.5,-0.5>, <0.5,0.5> to the triangles in the mesh.

Again we can omit all duplicate coordinates

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>,

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

uv_vectors {

9

<-0.5,-0.5>,<0,-0.5>, <0,0>,

/*as 1*/ <0.5,-0.5>,/*as 2*/

/*as 3*/ <0.5,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 4*/ <0.5,0.5>, /*as 2*/

/*as 5*/ <0,0.5>, /*as 2*/

/*as 6*/ <-0.5,0.5>,/*as 2*/

/*as 7*/ <-0.5,0>, /*as 2*/

/*as 8*/ /*as 0*/ /*as 2*/

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>,

<5,6,2>, <6,7,2>,

<7,8,2>, <8,0,2>

}

uv_mapping

pigment {wood scale 0.2}

}

Just as with the normal_vectors, if the number

of uv_vectors equals the number of vertices then the uv_indices{}

list is optional and the indices from the face_indices{} list

are used instead.

In contrary to the normal_indices list, if the uv_indices

list is used, the amount of indices should be equal to the amount of face_indices.

In the example below only 'one texture section' is specified and used on all triangles, using the

uv_indices.

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>,

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

uv_vectors {

3

<0,0>, <0.5,0>, <0.5,0.5>

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <1,3,2>,

<3,4,2>, <4,5,2>,

<5,6,2>, <6,7,2>,

<7,8,2>, <8,0,2>

}

uv_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>, <0,1,2>,

<0,1,2>, <0,1,2>,

<0,1,2>, <0,1,2>,

<0,1,2>, <0,1,2>

}

uv_mapping

pigment {gradient x scale 0.2}

}

A separate texture per triangle

By using the texture_list it is possible to specify a texture per triangle

or even per vertex in the mesh. In the latter case the three textures per triangle will

be interpolated. To let POV-Ray know what texture to apply to a triangle, the index of a

texture is added to the face_indices list, after the face index it belongs to.

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

texture_list {

2,

texture{pigment{rgb<0,0,1>}}

texture{pigment{rgb<1,0,0>}}

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>,0, <1,3,2>,1,

<3,4,2>,0, <4,5,2>,1,

<5,6,2>,0, <6,7,2>,1,

<7,8,2>,0, <8,0,2>,1

}

}

To specify a texture per vertex, three texture_list indices are added after

the face_indices

mesh2 {

vertex_vectors {

9,

<0,0,0>, <0.5,0,0>, <0.5,0.5,0>,

<1,0,0>, <1,0.5,0>, <1,1,0>

<0.5,1,0>, <0,1,0>, <0,0.5,0>

}

texture_list {

3,

texture{pigment{rgb <0,0,1>}}

texture{pigment{rgb 1}}

texture{pigment{rgb <1,0,0>}}

}

face_indices {

8,

<0,1,2>,0,1,2, <1,3,2>,1,0,2,

<3,4,2>,0,1,2, <4,5,2>,1,0,2,

<5,6,2>,0,1,2, <6,7,2>,1,0,2,

<7,8,2>,0,1,2, <8,0,2>,1,0,2

}

}

Assigning a texture based on the texture_list and texture

interpolation is done on a per triangle base. So it is possible to mix

triangles with just one texture and triangles with three textures in a mesh.

It is even possible to mix in triangles without any texture indices, these

will get their texture from a general texture statement in the

mesh2. uv_mapping is supported for texturing using a texture_list.

Polygon Object

The polygon object can be used to create any planar, n-sided

shapes like squares, rectangles, pentagons, hexagons, octagons, etc.

A polygon is defined by a number of points that describe its shape. Since polygons have to be closed the first point has to be repeated at the end of the point sequence.

In the following example we will create the word "POV" using just one polygon statement.

We start with thinking about the points we need to describe the desired shape. We want the letters to lie in the x-y-plane with the letter O being at the center. The letters extend from y=0 to y=1. Thus we get the following points for each letter (the z coordinate is automatically set to zero).

Letter P (outer polygon):

<-0.8, 0.0>, <-0.8, 1.0>,

<-0.3, 1.0>, <-0.3, 0.5>,

<-0.7, 0.5>, <-0.7, 0.0>

Letter P (inner polygon):

<-0.7, 0.6>, <-0.7, 0.9>,

<-0.4, 0.9>, <-0.4, 0.6>

Letter O (outer polygon):

<-0.25, 0.0>, <-0.25, 1.0>,

< 0.25, 1.0>, < 0.25, 0.0>

Letter O (inner polygon):

<-0.15, 0.1>, <-0.15, 0.9>,

< 0.15, 0.9>, < 0.15, 0.1>

Letter V:

<0.45, 0.0>, <0.30, 1.0>,

<0.40, 1.0>, <0.55, 0.1>,

<0.70, 1.0>, <0.80, 1.0>,

<0.65, 0.0>

Both letters P and O have a hole while the letter V consists of only one polygon. We will start with the letter V because it is easier to define than the other two letters.

We create a new file called polygdem.pov and add the following

text.

camera {

orthographic

location <0, 0, -10>

right 1.3 * 4/3 * x

up 1.3 * y

look_at <0, 0.5, 0>

}

light_source { <25, 25, -100> color rgb 1 }

polygon {

8,

<0.45, 0.0>, <0.30, 1.0>, // Letter "V"

<0.40, 1.0>, <0.55, 0.1>,

<0.70, 1.0>, <0.80, 1.0>,

<0.65, 0.0>,

<0.45, 0.0>

pigment { color rgb <1, 0, 0> }

}

As noted above the polygon has to be closed by appending the first point to the point sequence. A closed polygon is always defined by a sequence of points that ends when a point is the same as the first point.

After we have created the letter V we will continue with the letter P. Since it has a hole we have to find a way of cutting this hole into the basic shape. This is quite easy. We just define the outer shape of the letter P, which is a closed polygon, and add the sequence of points that describes the hole, which is also a closed polygon. That is all we have to do. There will be a hole where both polygons overlap.

In general we will get holes whenever an even number of sub-polygons inside a single polygon statement overlap. A sub-polygon is defined by a closed sequence of points.

The letter P consists of two sub-polygons, one for the outer shape and one for the hole. Since the hole polygon overlaps the outer shape polygon we will get a hole.

After we have understood how multiple sub-polygons in a single polygon statement work, it is quite easy to add the missing O letter.

Finally, we get the complete word POV.

polygon {

30,

<-0.8, 0.0>, <-0.8, 1.0>, // Letter "P"

<-0.3, 1.0>, <-0.3, 0.5>, // outer shape

<-0.7, 0.5>, <-0.7, 0.0>,

<-0.8, 0.0>,

<-0.7, 0.6>, <-0.7, 0.9>, // hole

<-0.4, 0.9>, <-0.4, 0.6>,

<-0.7, 0.6>

<-0.25, 0.0>, <-0.25, 1.0>, // Letter "O"

< 0.25, 1.0>, < 0.25, 0.0>, // outer shape

<-0.25, 0.0>,

<-0.15, 0.1>, <-0.15, 0.9>, // hole

< 0.15, 0.9>, < 0.15, 0.1>,

<-0.15, 0.1>,

<0.45, 0.0>, <0.30, 1.0>, // Letter "V"

<0.40, 1.0>, <0.55, 0.1>,

<0.70, 1.0>, <0.80, 1.0>,

<0.65, 0.0>,

<0.45, 0.0>

pigment { color rgb <1, 0, 0> }

}

Other Shapes

Blob Object

Blobs are described as spheres and cylinders covered with "goo" which stretches to smoothly join them (see section "Blob").

Ideal for modeling atoms and molecules, blobs are also powerful tools for creating many smooth flowing "organic" shapes.

A slightly more mathematical way of describing a blob would be to say that it is one object made up of two or more component pieces. Each piece is really an invisible field of force which starts out at a particular strength and falls off smoothly to zero at a given radius. Where ever these components overlap in space, their field strength gets added together (and yes, we can have negative strength which gets subtracted out of the total as well). We could have just one component in a blob, but except for seeing what it looks like there is little point, since the real beauty of blobs is the way the components interact with one another.

Let us take a simple example blob to start. Now, in fact there are a couple different types of components but we will look at them a little later. For the sake of a simple first example, let us just talk about spherical components. Here is a sample POV-Ray code showing a basic camera, light, and a simple two component blob:

#include "colors.inc"

background{White}

camera {

angle 15

location <0,2,-10>

look_at <0,0,0>

}

light_source { <10, 20, -10> color White }

blob {

threshold .65

sphere { <.5,0,0>, .8, 1 pigment {Blue} }

sphere { <-.5,0,0>,.8, 1 pigment {Pink} }

finish { phong 1 }

}

The threshold is simply the overall strength value at which the blob becomes visible. Any points within the blob where the strength matches the threshold exactly form the surface of the blob shape. Those less than the threshold are outside and those greater than are inside the blob.

We note that the spherical component looks a lot like a simple sphere object. We have the sphere keyword, the vector representing the location of the center of the sphere and the float representing the radius of the sphere. But what is that last float value? That is the individual strength of that component. In a spherical component, that is how strong the component's field is at the center of the sphere. It will fall off in a linear progression until it reaches exactly zero at the radius of the sphere.

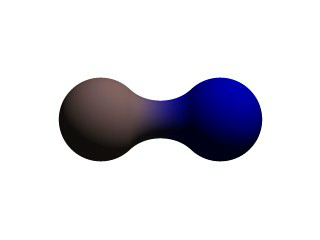

Before we render this test image, we note that we have given each component a different pigment. POV-Ray allows blob components to be given separate textures. We have done this here to make it clearer which parts of the blob are which. We can also texture the whole blob as one, like the finish statement at the end, which applies to all components since it appears at the end, outside of all the components. We render the scene and get a basic kissing spheres type blob.

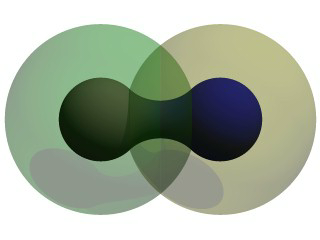

The image we see shows the spheres on either side, but they are smoothly joined by that bridge section in the center. This bridge represents where the two fields overlap, and therefore stay above the threshold for longer than elsewhere in the blob. If that is not totally clear, we add the following two objects to our scene and re-render. We note that these are meant to be entered as separate sphere objects, not more components in the blob.

sphere { <.5,0,0>, .8

pigment { Yellow transmit .75 }

}

sphere { <-.5,0,0>, .8

pigment { Green transmit .75 }

}

Now the secrets of the kissing spheres are laid bare. These semi-transparent spheres show where the components of the blob actually are. If we have not worked with blobs before, we might be surprised to see that the spheres we just added extend way farther out than the spheres that actually show up on the blobs. That of course is because our spheres have been assigned a starting strength of one, which gradually fades to zero as we move away from the sphere's center. When the strength drops below the threshold (in this case 0.65) the rest of the sphere becomes part of the outside of the blob and therefore is not visible.

See the part where the two transparent spheres overlap? We note that it exactly corresponds to the bridge between the two spheres. That is the region where the two components are both contributing to the overall strength of the blob at that point. That is why the bridge appears: that region has a high enough strength to stay over the threshold, due to the fact that the combined strength of two spherical components is overlapping there.

Component Types and Other New Features

The shape shown so far is interesting, but limited. POV-Ray has a few extra tricks that extend its range of usefulness however. For example, as we have seen, we can assign individual textures to blob components, we can also apply individual transformations (translate, rotate and scale) to stretch, twist, and squash pieces of the blob as we require. And perhaps most interestingly, the blob code has been extended to allow cylindrical components.

Before we move on to cylinders, it should perhaps be mentioned that the old style of components used in previous versions of POV-Ray still work. Back then, all components were spheres, so it was not necessary to say sphere or cylinder. An old style component had the form:

component Strength, Radius, <Center>

This has the same effect as a spherical component, just as we already saw above. This is only useful for backwards compatibility. If we already have POV-Ray files with blobs from earlier versions, this is when we would need to recognize these components. We note that the old style components did not put braces around the strength, radius and center, and of course, we cannot independently transform or texture them. Therefore if we are modifying an older work into a new version, it may arguably be of benefit to convert old style components into spherical components anyway.

Now for something new and different: cylindrical components. It could be argued that all we ever needed to do to make a roughly cylindrical portion of a blob was string a line of spherical components together along a straight line. Which is fine, if we like having extra to type, and also assuming that the cylinder was oriented along an axis. If not, we would have to work out the mathematical position of each component to keep it is a straight line. But no more! Cylindrical components have arrived.

We replace the blob in our last example with the following and re-render. We can get rid of the transparent spheres too, by the way.

blob {

threshold .65

cylinder { <-.75,-.75,0>, <.75,.75,0>, .5, 1 }

pigment { Blue }

finish { phong 1 }

}

We only have one component so that we can see the basic shape of the cylindrical component. It is not quite a true cylinder - more of a sausage shape, being a cylinder capped by two hemispheres. We think of it as if it were an array of spherical components all closely strung along a straight line.

As for the component declaration itself: simple, logical, exactly as we would expect it to look (assuming we have been awake so far): it looks pretty much like the declaration of a cylinder object, with vectors specifying the two endpoints and a float giving the radius of the cylinder. The last float, of course, is the strength of the component. Just as with spherical components, the strength will determine the nature and degree of this component's interaction with its fellow components. In fact, next let us give this fellow something to interact with, shall we?

Complex Blob Constructs and Negative Strength

Beginning a new POV-Ray file, we enter this somewhat more complex example:

#include "colors.inc"

background{White}

camera {

angle 20

location<0,2,-10>

look_at<0,0,0>

}

light_source { <10, 20, -10> color White }

blob {

threshold .65

sphere{<-.23,-.32,0>,.43, 1 scale <1.95,1.05,.8>} //palm

sphere{<+.12,-.41,0>,.43, 1 scale <1.95,1.075,.8>} //palm

sphere{<-.23,-.63,0>, .45, .75 scale <1.78, 1.3,1>} //midhand

sphere{<+.19,-.63,0>, .45, .75 scale <1.78, 1.3,1>} //midhand

sphere{<-.22,-.73,0>, .45, .85 scale <1.4, 1.25,1>} //heel

sphere{<+.19,-.73,0>, .45, .85 scale <1.4, 1.25,1>} //heel

cylinder{<-.65,-.28,0>, <-.65,.28,-.05>, .26, 1} //lower pinky

cylinder{<-.65,.28,-.05>, <-.65, .68,-.2>, .26, 1} //upper pinky

cylinder{<-.3,-.28,0>, <-.3,.44,-.05>, .26, 1} //lower ring

cylinder{<-.3,.44,-.05>, <-.3, .9,-.2>, .26, 1} //upper ring

cylinder{<.05,-.28,0>, <.05, .49,-.05>, .26, 1} //lower middle

cylinder{<.05,.49,-.05>, <.05, .95,-.2>, .26, 1} //upper middle

cylinder{<.4,-.4,0>, <.4, .512, -.05>, .26, 1} //lower index

cylinder{<.4,.512,-.05>, <.4, .85, -.2>, .26, 1} //upper index

cylinder{<.41, -.95,0>, <.85, -.68, -.05>, .25, 1} //lower thumb

cylinder{<.85,-.68,-.05>, <1.2, -.4, -.2>, .25, 1} //upper thumb

pigment{ Flesh }

}

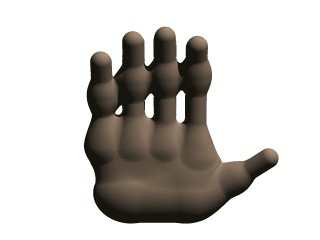

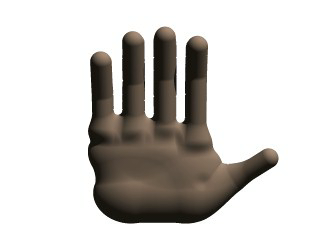

As we can guess from the comments, we are building a hand here. After we render this image, we can see there are a few problems with it. The palm and heel of the hand would look more realistic if we used a couple dozen smaller components rather than the half dozen larger ones we have used, and each finger should have three segments instead of two, but for the sake of a simplified demonstration, we can overlook these points. But there is one thing we really need to address here: This poor fellow appears to have horrible painful swelling of the joints!

A review of what we know of blobs will quickly reveal what went wrong. The joints are places where the blob components overlap, therefore the combined strength of both components at that point causes the surface to extend further out, since it stays over the threshold longer. To fix this, what we need are components corresponding to the overlap region which have a negative strength to counteract part of the combined field strength. We add the following components to our blob.

sphere{<-.65,.28,-.05>, .26, -1} //counteract pinky knucklebulge

sphere{<-.65,-.28,0>, .26, -1} //counteract pinky palm bulge

sphere{<-.3,.44,-.05>, .26, -1} //counteract ring knuckle bulge

sphere{<-.3,-.28,0>, .26, -1} //counteract ring palm bulge

sphere{<.05,.49,-.05>, .26, -1} //counteract middle knuckle bulge

sphere{<.05,-.28,0>, .26, -1} //counteract middle palm bulge

sphere{<.4,.512,-.05>, .26, -1} //counteract index knuckle bulge

sphere{<.4,-.4,0>, .26, -1} //counteract index palm bulge

sphere{<.85,-.68,-.05>, .25, -1} //counteract thumb knuckle bulge

sphere{<.41,-.7,0>, .25, -.89} //counteract thumb heel bulge

Much better! The negative strength of the spherical components counteracts approximately half of the field strength at the points where to components overlap, so the ugly, unrealistic (and painful looking) bulging is cut out making our hand considerably improved. While we could probably make a yet more realistic hand with a couple dozen additional components, what we get this time is a considerable improvement. Any by now, we have enough basic knowledge of blob mechanics to make a wide array of smooth, flowing organic shapes!

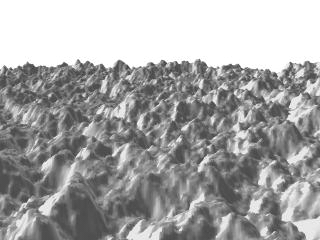

Height Field Object

A height_field is an object that has a surface that is

determined by the color value or palette index number of an image designed

for that purpose. With height fields, realistic mountains and other types of

terrain can easily be made. First, we need an image from which to create the

height field. It just so happens that POV-Ray is ideal for creating such an

image.

We make a new file called image.pov and edit it to contain the

following:

#include "colors.inc"

global_settings {

assumed_gamma 2.2

hf_gray_16

}

The hf_gray_16 keyword causes the output to be in a special

16 bit grayscale that is perfect for generating height fields. The normal 8

bit output will lead to less smooth surfaces.

Now we create a camera positioned so that it points directly down the z-axis at the origin.

camera {

location <0, 0, -10>

look_at 0

}

We then create a plane positioned like a wall at z=0. This plane will completely fill the screen. It will be colored with white and gray wrinkles.

plane { z, 10

pigment {

wrinkles

color_map {

[0 0.3*White]

[1 White]

}

}

}

Finally, create a light source.

light_source { <0, 20, -100> color White }

We render this scene at 640x480 +A0.1 +FT.

We will get an image that will produce an excellent height field. We create a

new file called hfdemo.pov and edit it as follows:

Note: Windows users, unless you specify +FT as above,

you will get a .BMP file (which is the default Windows version output).

In this case you will need to use sys instead of

tga in the height_field statement below.

#include "colors.inc"

We add a camera that is two units above the origin and ten units back ...

camera{

location <0, 2, -10>

look_at 0

angle 30

}

... and a light source.

light_source{ <1000,1000,-1000> White }

Now we add the height field. In the following syntax, a Targa image file is specified, the height field is smoothed, it is given a simple white pigment, it is translated to center it around the origin and it is scaled so that it resembles mountains and fills the screen.

height_field {

tga "image.tga"

smooth

pigment { White }

translate <-.5, -.5, -.5>

scale <17, 1.75, 17>

}

We save the file and render it at 320x240 -A. Later, when we

are satisfied that the height field is the way we want it, we render it at a

higher resolution with anti-aliasing.

Wow! The Himalayas have come to our computer screen!

Isosurface Object

Isosurfaces are shapes described by mathematical functions.

In contrast to the other mathematically based shapes in POV-Ray, isosurfaces are approximated during rendering and therefore they are sometimes more difficult to handle. However, they offer many interesting possibilities, like real deformations and surface displacements

Some knowledge about mathematical functions and geometry is useful, but not necessarily required to work with isosurfaces.

| Text Object | Simple functions |

|

This document is protected, so submissions, corrections and discussions should be held on this documents talk page. |