Difference between revisions of "User:Clipka/Gamma"

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

== Why Does POV-Ray Not Do it The Photoshop Way? == | == Why Does POV-Ray Not Do it The Photoshop Way? == | ||

| − | With raytracing being essentially an attempt to simulate the ''physical'' interaction of light rays with object surfaces and media, it should come as no surprise that the math behind it is easiest (and fastest) when brightness levels are expressed as ''physical light intensity'', rather than ''perceptual'' brightness (which varies with viewing conditions anyway) or the more or less arbitrary concept of pixel values. To get realistic results at reasonable speed, a raytracing system ''must'' do virtually all its internal computations with physical light intensity. | + | With raytracing being essentially an attempt to simulate the ''physical'' interaction of light rays with object surfaces and media, it should come as no surprise that the math behind it is easiest (and fastest) when brightness levels are expressed as ''physical light intensity'', rather than ''perceptual'' brightness (which varies with viewing conditions anyway) or the more or less arbitrary concept of ''pixel values''. To get realistic results at reasonable speed, a raytracing system ''must'' do virtually all its internal computations with physical light intensity. |

Still, in theory this would not stop us from having the user specify all colors by pixel values, and automatically convert to physical light intensity just as the macro above does. So why does POV-Ray not do it? | Still, in theory this would not stop us from having the user specify all colors by pixel values, and automatically convert to physical light intensity just as the macro above does. So why does POV-Ray not do it? | ||

Revision as of 18:27, 26 March 2010

What is this Gamma Thing All About?

In short, the whole "gamma issue" is about nonlinearity in image processing, regarding how intermediate brightness levels between 0% and 100% are interpreted.

To let you take a first brief glimpse at the can of worms we're about to open: A standard 8-bit image file has pixel values ranging from 0 to 255, equivalent to 0% and 100% brightness respectively. So what brightness would you expect for a value of 128? Well, 50%, right? Wrong. A meager 22% is usually closer to the mark. Or 20%, or 25%, or whatever exactly your system happens to make of it. Unless we're talking about percieved brightness: A physical light intensity of 22% actually looks surprisingly bright, and an observer may percieve it as something around 45% in between black and white. Depending on ambient viewing conditions, just to make matters worse.

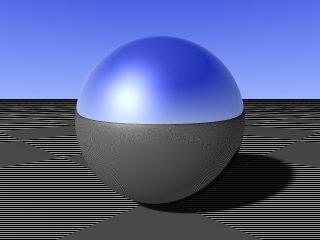

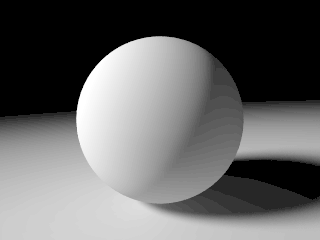

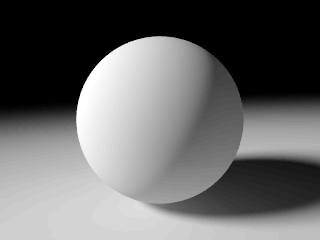

For a raytracing engine, linear physical light intensity is the only useful internal representation of intermediate brightness values, as it is in this domain that computations can be performed most efficiently; and any attempt to apply the same math in some other domain will produce inconsistencies in the output, which will usually be subtle enough to be unable to pinpoint them, yet obvious enough for an observer to somehow sense that something is wrong.

However, wherever the engine interfaces to the "outside world"—whether generating the output image file, submitting preview window content to the operating system for display, loading some input image for texturing, or just having the user enter color values picked from some other application—a raytracing software package has to account for the "gamma issue", or the output will still be just as wrong: Input colors will not be interpreted as intended, and the output image will not appear as computed.

Perceptual Brightness and Gamma Encoding

You may wonder why pixel values represent brightness levels (and thus colors) in such a strongly non-linear fashion—and why you probably never noticed before. However, if you have read the introduction carefully you may already guess the answer to the second question, which in fact also leads to the answer to the first one: The "pixel value way" of encoding brightness levels—known as gamma encoding—is much closer to how a human observer percieves brightness levels. For instance, while a human can easily distinguish a 1%-intensity grey from a 0%-intensity black, he is perfectly unable to tell a 99%-intensity grey from a 100%-intensity white. As a result, gamma encoding can get away with a lower bit depth than linear encoding.

In its simplest form, gamma encoding is based on a straightforward power-law function (aka gamma function, hence the name), i.e.:

where is either:

- the encoding gamma when encoding from linear brightness values, or

- the decoding gamma—being the inverse of the encoding gamma—when decoding to linear brightness values.

A typical encoding gamma would be somewhere around 0.45, with the decoding gamma consequently being somewhere around 2.2.

Another popular function used in this role is the sRGB transfer function. It can roughly be approximated by a classic power-law function with a decoding gamma of 2.2, but has slightly superior properties at very low brightness levels. As the name suggests, it is an integral part of the sRGB color space, which is the officially recommended standard color space for the World Wide Web.

Display Gamma and Pre-Correction

To get the history straight, storage efficiency is probably not the main reason why gamma encoding originally evolved in the first place. Instead, it seems to have been around ever since the first use of multiple brightness levels in computer displays, and is more likely due to the inherent power-law response curve of cathode ray tubes, which just happens to fit quite well with the peculiarities of human vision. To minimize hardware complexity, the graphics adaptor would use linear DACs to proportionally convert color data to signal voltages for the display, which in turn would more or less directly drive its CRT from these signals; without any electronics to compensate for the nonlinearity of the CRT, the color data would have to be pre-corrected for the display subsystem's inherent display gamma.

A typical display gamma is somewhere around 2.2 on PC systems (remember that value?), and 1.8 on Mac systems prior to Mac OS X 10.6 (the proper pre-correction would consist of applying a power-law function with a gamma of 0.45 or 0.56 respectively, but in this context it is more common to specify the display gamma to correct for). There is a wide bandwidth though, especially in the heterogenous PC world, as an arbitrary system's exact gamma depends on the particular combination of graphics card, display, and individual display settings like brightness and contrast. In professional image-processing environments, it is therefore customary to calibrate a computer's display subsystem to match a certain well-defined overall gamma.

While the non-linear response curve is a CRT-typical phenomen that is not inherent in LCD panels, LCD-based displays are typically equipped with circuitry to deliberately achieve a CRT-like gamma—possibly not only for the sake of compatibility, but also for efficient use of digital interfaces.

File Gamma

As mentioned before, the nonlinearity in CRTs happens to roughly coincide with the nonlinearity in human vision, so that the same mathematical transformation traditionally required to pre-correct color data for the graphics hardware also happens to provide a more efficient encoding. It should therefore come as no surprise that image files have a long tradition of not storing linear light intensity data, but rather gamma pre-corrected—and thereby also gamma-encoded—color values.

The downside to this is that gamma pre-correction is inherently system-specific in nature, and therefore an image pre-corrected to fit one computer's display gamma may not fit another one's; and while in a professional environment there would usually be a standard to which all computers would have been calibrated, this standard might still differ between individual organizations. As a consequence, most older file formats do use gamma encoding in practice, but allow for broad variations in the encoding gamma.

Fortunately, the situation has improved a lot recently, as image viewing software starts taking over the responsibility for properly pre-correcting the image data to be fed into the graphics card, reducing the importance of gamma in image files to that of mere gamma encoding. At the same time, the normative power of the World Wide Web has been pushing the sRGB color space—and with it the sRGB transfer function—as the de-facto encoding standard for virtually all major file formats that traditionally carried pre-corrected content.

Various file formats have also been extended to optionally carry meta-information about the encoding gamma or color space used, although in practice such features are only used for a small subset of the major file formats. One notable example is the PNG file format.

A recent development in another direction are high dynamic range image file formats, which employ floating-point or floating-point-alike number formats to represent light intensity values in a vast range far exceeding that of traditional file formats. As a side effect they can get away without gamma encoding, and are therefore explicitly defined to store linear light intensity levels, avoiding both unnecessary processing steps and the potential confusion associated with gamma.

Under Construction From Here On

Why Should I Care?

Even as a POV-Ray beginner, you'll possibly care about the general phenomenon: The 50% vs. 22% vs. 45% thing - pixel values and perceptual brightness vs. physical light intensity. These differences have two major implications for you:

- Colors you pick in Photoshop (or Gimp or whatever your favorite image processing software may be) will not seem to work in POV-Ray as expected; grey-ish colors will simply appear too bright, while more colorful ones will appear washed out, or even off hue (this is because the nonlinearity affects each color component individually).

- When trying to achieve a certain brightness level, you may have difficulties getting the level right at first attempt.

As an advanced POV-Ray user, you may also worry about different systems exhibiting more or less subtle differences in the nonlinearity:

- The same image file may display differently on a friend's computer. Or the new LCD you're about to buy. Or the machine you're running your overnight renders on. Or the computers of the jurors of that internet ray tracing competition you're taking part in. You probably want to make sure they can see the barely-lit creature lurking in your nighttime scene, or that your daytime scene doesn't look too washed-out on their displays. Presuming they have done their own gamma homework of course.

- You want to be sure that the scene you share across the internet renders on the recipient's computer just as it does on your own.

So What Can I Do About Those Color Picking Issues?

When picking pixel values from Photoshop (or whatever you have), you can use the following formula to compute the color parameters to use in your POV-Ray scene file:

If you frequently pick colors, you may also want to define a macro to do the job:

#macro PickedRGB(R,G,B)

#local Red = pow(R/255, 2.2);

#local Green = pow(G/255, 2.2);

#local Blue = pow(B/255, 2.2);

rgb <Red,Green,Blue>

#end

#local MyColor = color PickedRGB(255,128,0);

If you generally feel more at home with defining colors by pixel values rather than physical brightness levels, you can use the same macro of course for all your colors, not just those you picked from some image-editing application.

Why Does POV-Ray Not Do it The Photoshop Way?

With raytracing being essentially an attempt to simulate the physical interaction of light rays with object surfaces and media, it should come as no surprise that the math behind it is easiest (and fastest) when brightness levels are expressed as physical light intensity, rather than perceptual brightness (which varies with viewing conditions anyway) or the more or less arbitrary concept of pixel values. To get realistic results at reasonable speed, a raytracing system must do virtually all its internal computations with physical light intensity.

Still, in theory this would not stop us from having the user specify all colors by pixel values, and automatically convert to physical light intensity just as the macro above does. So why does POV-Ray not do it?

The answer lies in the power of the scene description language: You can do too much with colors in POV-Ray's SDL that it is practically imposible to come up with a watertight automatism of identifying which non-color value specified in a scene file will wind up being interpeted as a color nonetheless (and therefore would have to be subject to conversion), which color value will end up being interpreted as a non-color (and therefore would have to be exempt from conversion), and whether some mathematical operation on colors should be performed in the pixel value domain or in the light intensity domain instead.

POV-Ray's philosophy therefore is to always presume colors to be expressed by linear light intensity values, and leave it up to the user to explicitly specify when and where conversions are to be applied.

So What Can I Do About Those System-Dependent Differences?

In a nutshell, the answer is: Calibrate your system, and encourage others to do the same.